We would like to acknowledge and thank our co-branding partners for their contributions to this project:

Nuestras Voces Adelante

The National LGBTQI+ Cancer Network

Cervivor

About Cervical Cancer Awareness Month

January is National Cervical Cancer Awareness Month, which aims to raise awareness of cervical cancer and promote information on prevention, diagnosis, treatment, survivorship, and cure. This toolkit can assist your organization in sharing important information with your networks about cervical cancer.

Data and Statistics

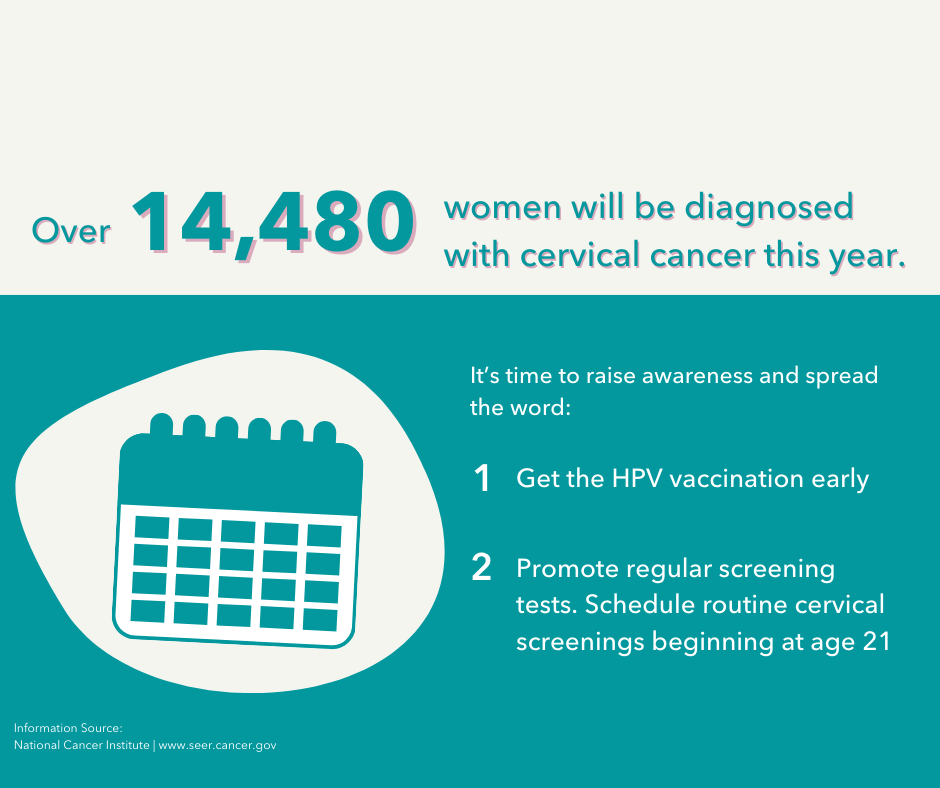

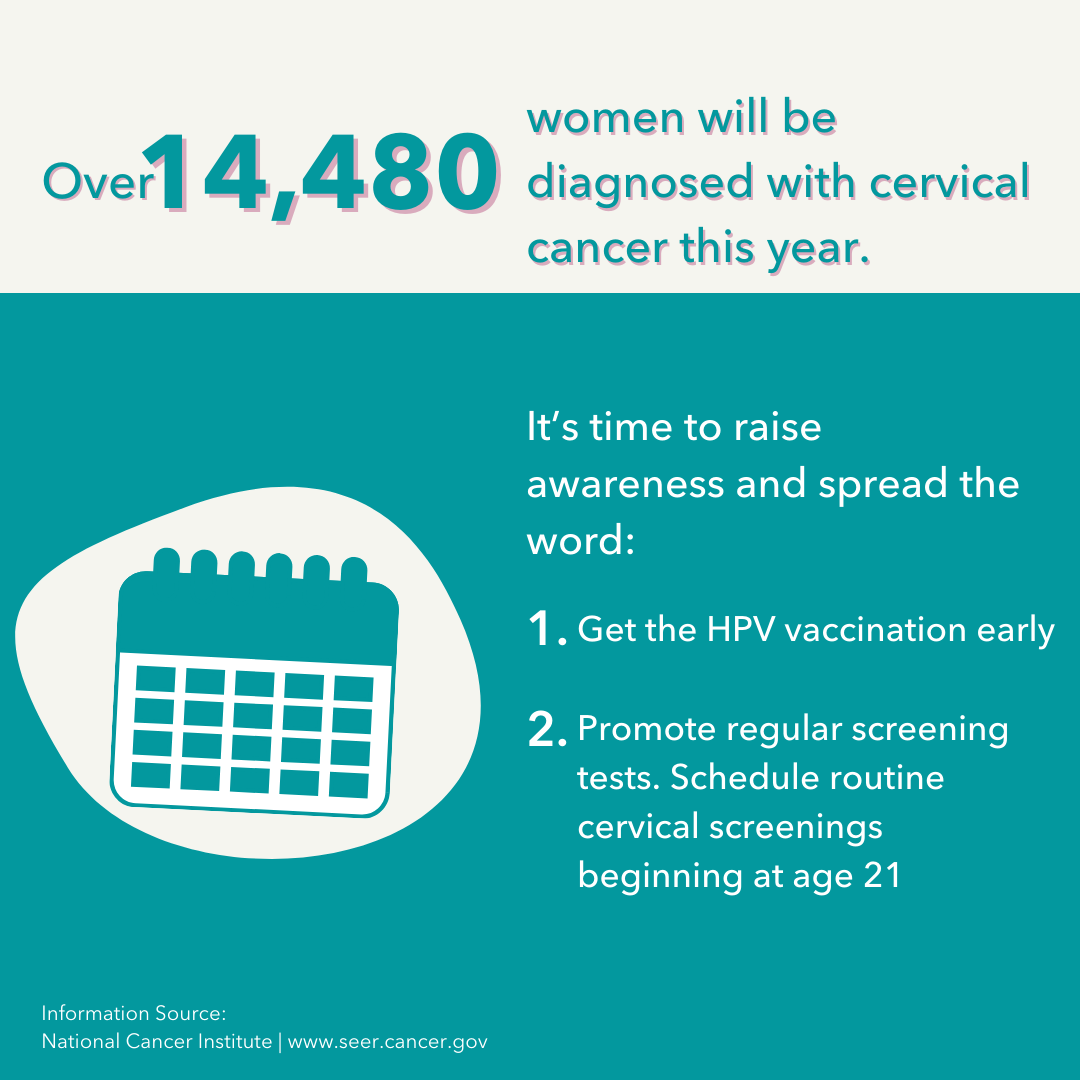

In 2021, the latest year in which incidence data are available, 12,536 new cervical cancers were reported in the United States.[1] For every 100,000 individuals, 7 new cervical cancers were reported.[2] In 2022, the latest year in which data are available, 4,051 individuals died of cervical cancer.[3] Because of health service disruptions throughout 2020 and 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, cervical cancer screening, diagnosis, and central cancer registry reporting may be delayed, and actual cancer occurrence may be underreported.

| *Note about terminology: Here we report statistics the way in which they are reported in our source references, while emphasizing their limitations. Data are currently reported as binary sex data (male or female) and ignore gender and sex characteristic differences that make up the intersex spectrum, making it difficult to explain differences across gender and sexual orientations. While the latest North American Association of Central Cancer Registries (NAACCR) data dictionary includes multiple options beyond sex variables, the field may be underused or underreported. We advocate for systematic collection of sex assigned at birth, gender identity, sexual orientation, and intersex status to inform and advance evidence-based guidelines. We use gender-neutral language when possible. Until better data are available, it is reasonable to assume sex and gender are conflated in most data sources. |

Screening

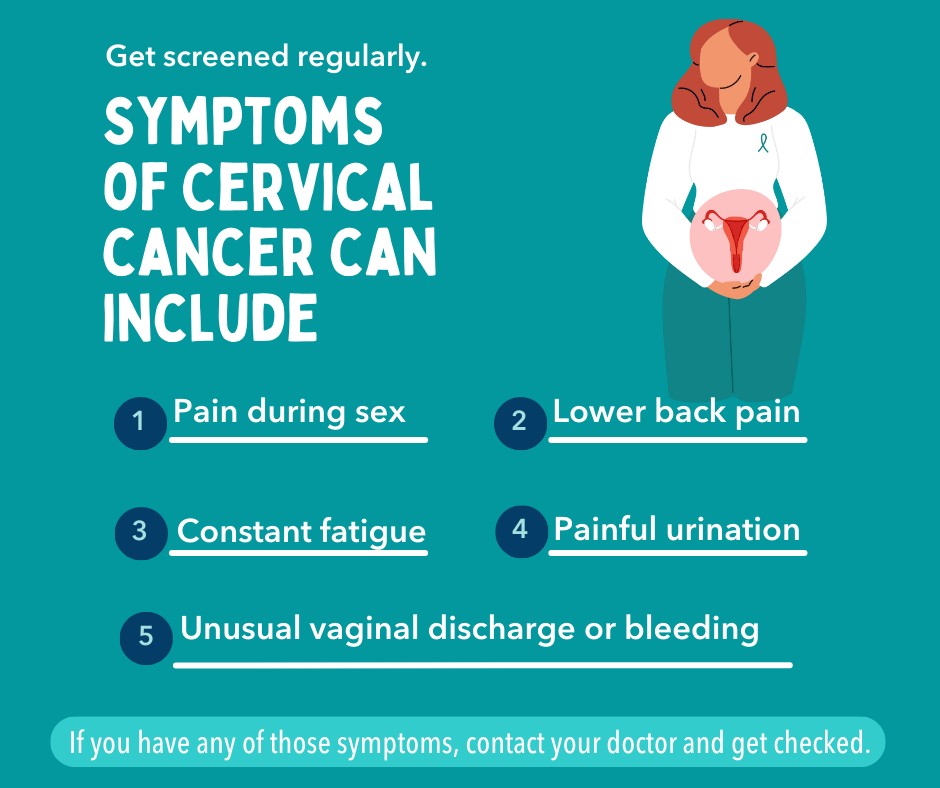

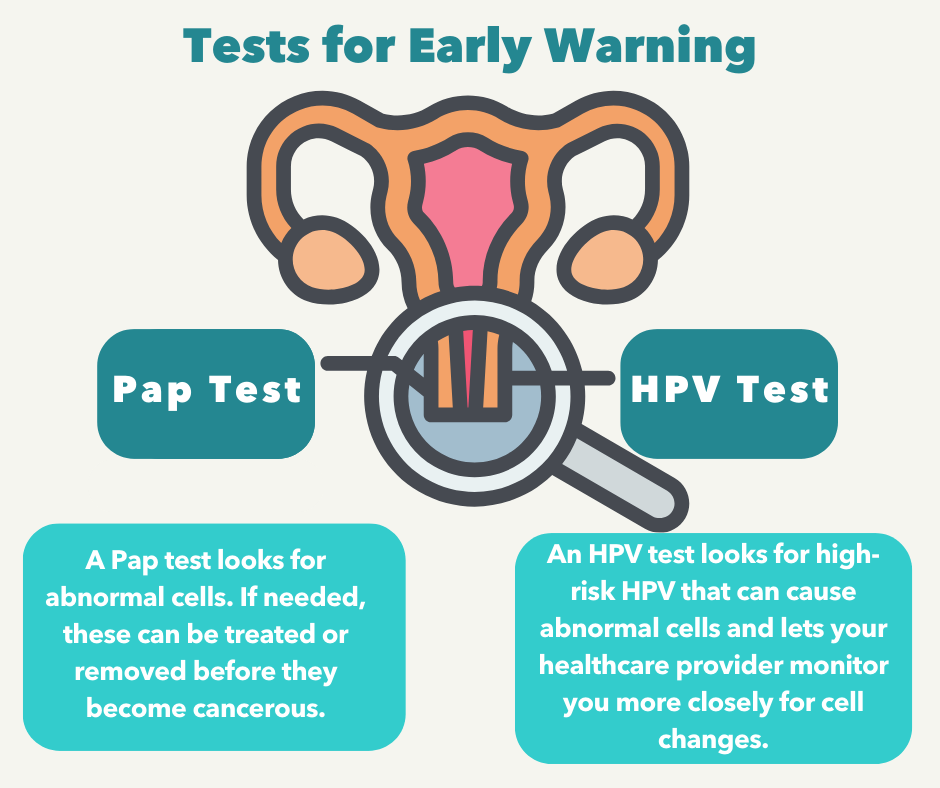

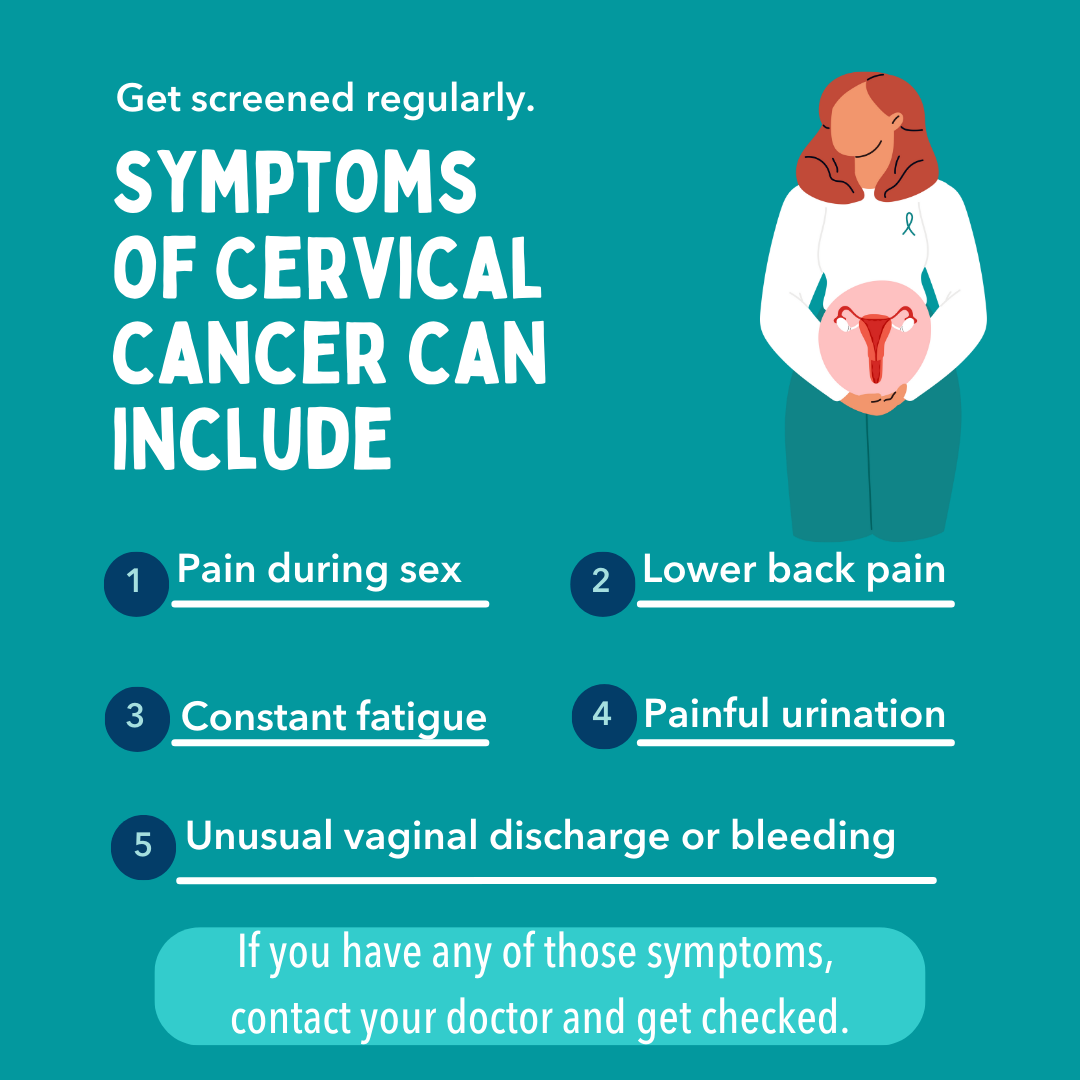

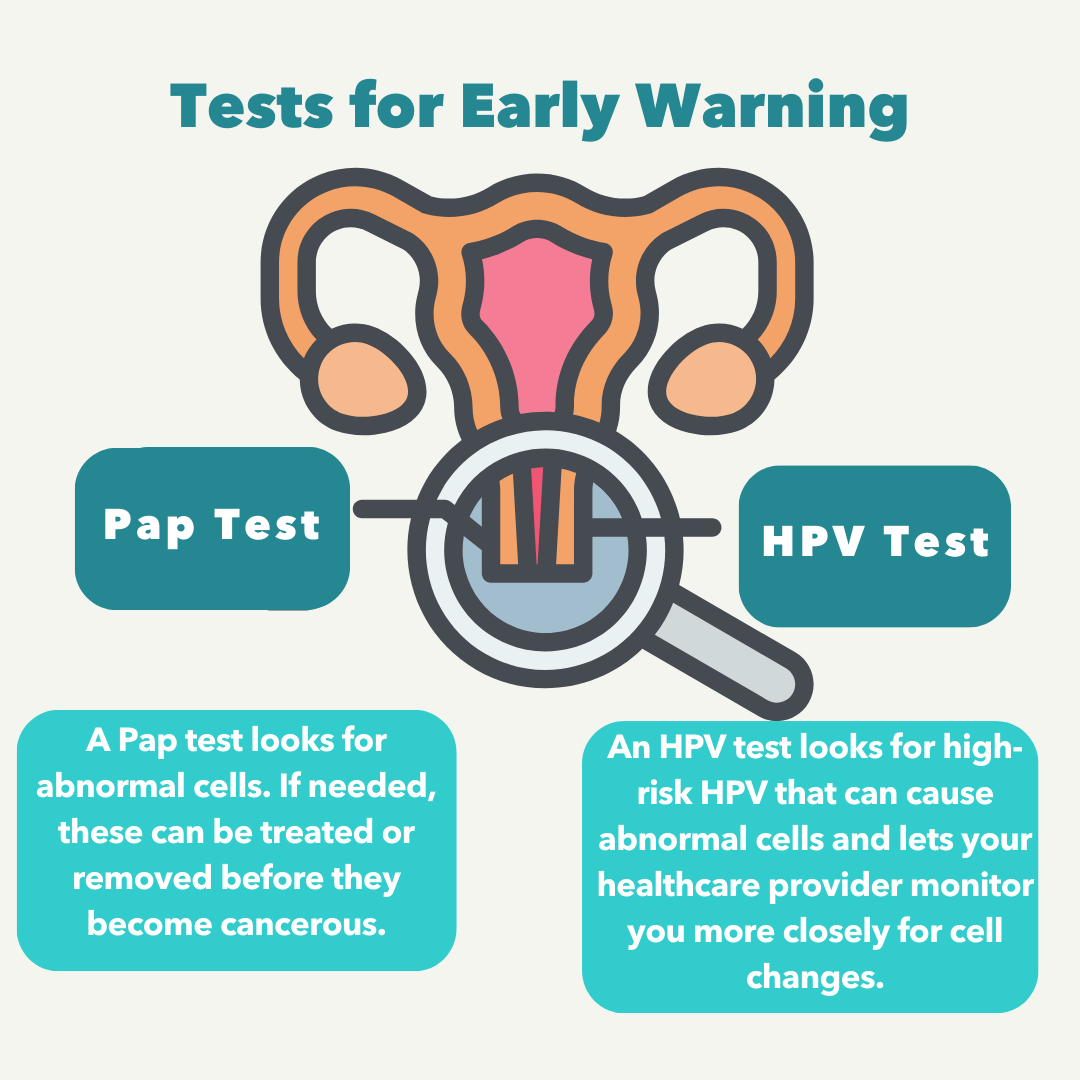

Screening with a Pap test, also known as a Pap smear or Papanicolaou test, for the human papillomavirus (HPV), and HPV vaccination are proven tools for reducing the burden of cervical cancer.[4] When there are cervical cells that look abnormal but are not yet cancerous, it is called cervical precancer. These abnormal cells may be the first sign of cancer that develops years later. Cervical precancer usually doesn’t cause pain or other symptoms.[5]

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) (2024) recommends:

- Clinicians screen women ages 21 to 29 every 3 years with a Pap test.

- For women ages 30 to 65, the Task Force recommends screening with an HPV test every 5 years.

- Alternative effective screening options for women 30 to 65 include getting a Pap test every 3 years or getting a combined HPV and Pap test every 5 years, also known as co-testing.[6]

The draft USPSTF recommendation for Screening for Cervical Cancer, released December 10, 2024, emphasizes testing for high-risk human papillomaviruses, or HPV, as a primary screening approach for women ages 30 to 65. In 2024, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) expanded the approvals of two tests that detect cancer-causing types of HPV in the cervix. Both tests are used as part of screening for cervical cancer. These tests allow people the option to collect a vaginal sample themselves for HPV testing if they cannot have or do not want a pelvic exam. The collection involves a swab or brush and must be done in a health care setting, such as primary care offices, urgent care, pharmacies, and mobile clinics.[7] While patients may have the option to self-collect the cervical sample during an appointment at a healthcare facility, this should be a shared decision with a health care provider.[8]

Cervical cancer screening rates in the U.S. are generally high, yet certain groups experience disparities in screening and surveillance.[9] Healthcare providers are primary sources of information about cervical cancer screening for patients, and their recommendation is an important factor for influencing screening utilization and coverage.[10]

Despite successes in cervical cancer risk reduction through screening and vaccination, disparities in screening still exist across racial, ethnic and socioeconomic groups.[11] Follow-up care after an abnormal test remains low for Black, Hispanic, Asian and Pacific Islander people.[12]

Providers should promote awareness of cervical cancer screening and remind patients about the different types of results they could receive and explain what follow-up care involves.[13]

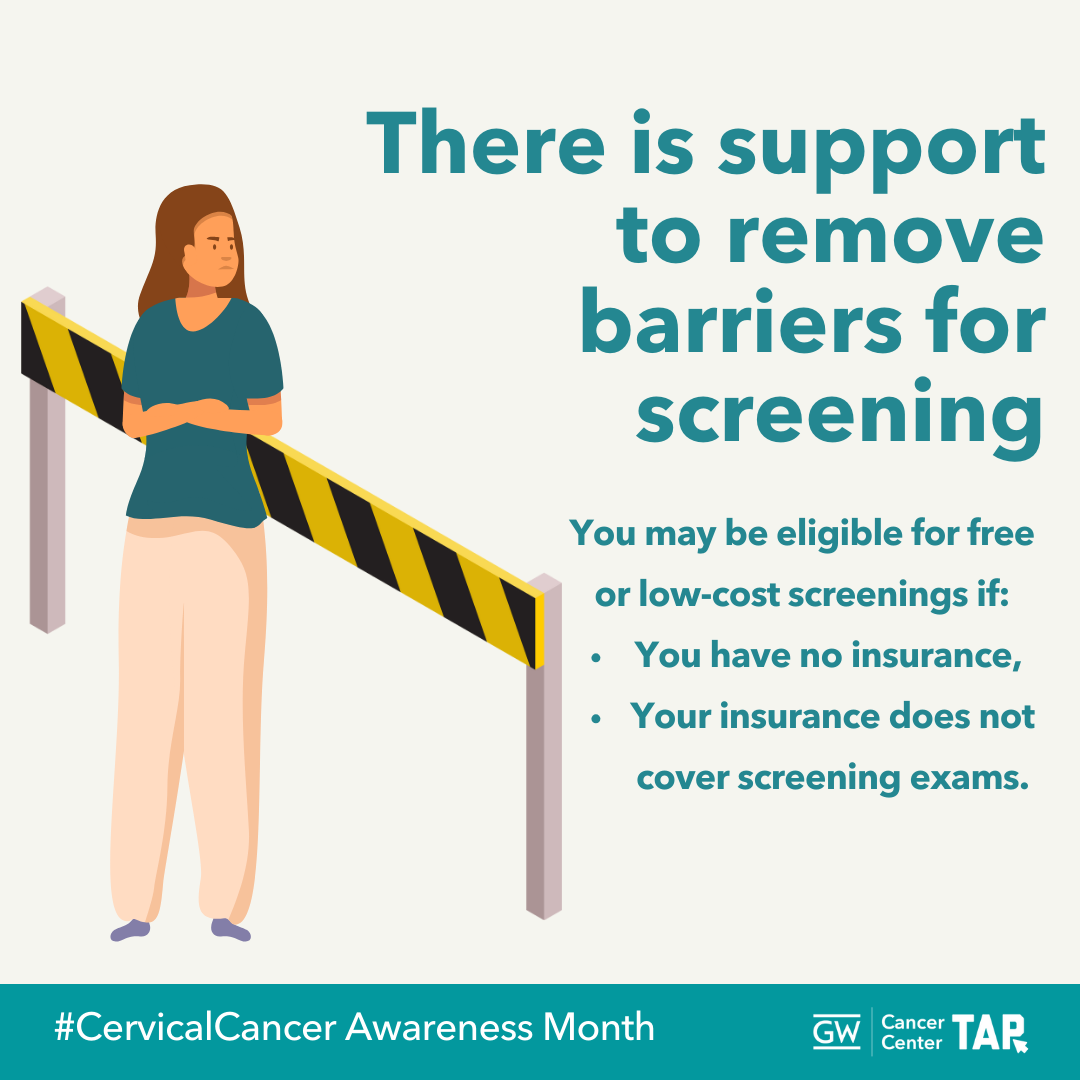

CDC’s National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP) provides breast and cervical cancer screenings and diagnostic services to those who have low incomes and are uninsured or underinsured. Check for eligibility and local screening programs here.[14]

HPV Vaccination

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a known cause of cervical cancer, responsible for 90% of cervical cancers, as well as anal, vaginal, vulvar, penile and oropharyngeal cancers.[15] About 10% of individuals who have HPV infections on their cervix will develop long-lasting infections that put them at risk for cervical cancer.[16] HPV vaccines have been used since 2006. HPV vaccines went through extensive safety testing before becoming available. Hundreds of million doses of the HPV vaccine have been given worldwide. Gardasil 9 is the only HPV vaccine available in the US.[17] Since the HPV vaccine was first used in the US in 2006, the percentage of cervical precancers caused by HPV types among vaccinated individuals has dropped 40%.[18] Healthcare provider recommendations are the leading reason for HPV vaccination uptake.[19]

HPV vaccination could prevent more than 90% of cancers caused by HPV—an estimated 33,700 cases every year.[20]

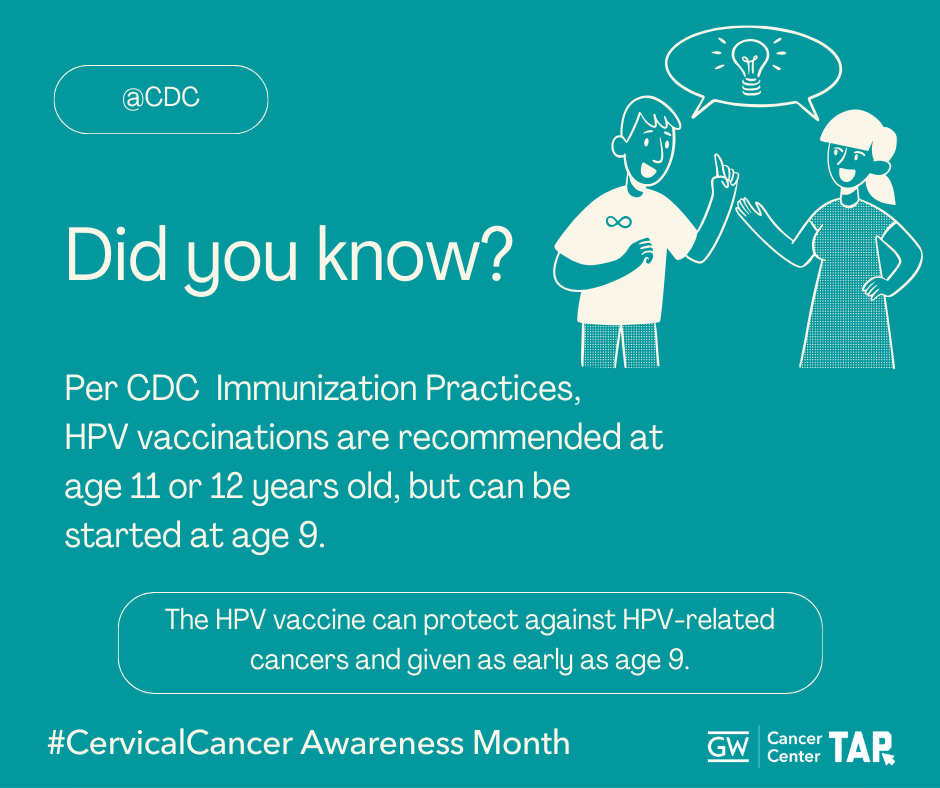

The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommend:

- HPV vaccine is recommended at age 11 or 12 years old, but it can be started at age 9.

- For children ages 9-12 years, the CDC recommends two doses of the HPV vaccine, the second dose should be given 6 to 12 months after the first.

- Three doses are recommended for persons who initiate the vaccination series at ages 15 through 26 years and for immunocompromised persons.

- For adults aged 27 through 45 years, the public health benefit of HPV vaccination in this age range is minimal; shared clinical decision-making is recommended because some persons might benefit.[21]

The HPV vaccine is licensed by the FDA for adolescents starting at age 9.[22] The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends beginning at the age of 9 to allow time for a child to receive both vaccine doses by age 13.[23] The CDC recommends it routinely for the 11- to 12-year-old age group. The data so far show that vaccinating at age 9 or 10 improves vaccination coverage at age 13. Also, it reduces the number of vaccines received at age 11, particularly when children are also receiving the flu vaccine during flu season.[24]

Receiving the vaccine well before there is skin-to-skin contact in the areas of high infection risk, allows the body more time to produce the strongest immune response against HPV when the vaccine is given in this age range. To spread the word about starting HPV vaccination at age nine, the National HPV Vaccination Roundtable created several resources to support health systems, healthcare providers, public health agencies, and health plans as part of the ‘Start at Age 9 Toolkit’ including resources for parents, print materials, and more. To view the National HPV Vaccination Roundtable’s videos on HPV vaccinations, click here.[25]

Best Practices for Communicating About Cervical Cancer

| Use gender-neutral language, when possible. Current data are collected on reported sex (based on only two options: male or female) and does not necessarily correlate with the gender identity of those affected by cancer. Ensure language is inclusive; reflect the words used by your patients to refer to themselves as terminology evolves and varies across communities. |

Emphasize screening information and follow-up reminders

- Increase knowledge of Pap test (cytology) and HPV screening for cervical cancer. Educational campaigns such as CDC’s Inside Knowledge campaign can improve patient and provider knowledge of Pap test and HPV screening for cervical cancer. Tools, resources and graphics can be found at CDC’s Cervical Cancer Resources to Share.

- Promote easy-to-understand information on cervical cancer screening recommendations.[26]

- Remind providers to promote screening as part of cervical cancer prevention.

- Promote awareness of cervical cancer screening widely, particularly for populations placed at the greatest risk using culturally tailored messaging.

- Remind patients to get screened regularly for cervical cancer and promote easy-to understand information on the latest screening recommendations.

- Emphasize and explain follow-up care if an abnormal lesion is identified.

- Develop language and culturally appropriate educational materials to address disparities in knowledge about cervical cancer and screening.

Remind providers about the importance of talking about HPV vaccination as cervical cancer prevention

- Improve knowledge of HPV-related cancers. Educational campaigns such as CDC’s Inside Knowledge campaign can improve patient and provider knowledge of HPV- associated gynecologic cancers. Tools, resources, and graphics can be found at CDC’s Cervical Cancer Resources to Share.

- Promote HPV vaccination as cervical cancer prevention.

- Remind providers about the importance of talking about HPV vaccination with parents of adolescents.

- Strong provider recommendations are associated with increased HPV vaccination rates. Providers’ recommendations about HPV vaccination should be clear and timely (when individuals are in the recommended age range for vaccination), consistent with other vaccine recommendations.

- Equip providers with effective recommendation scripts, such as “today your child should have three vaccines. They’re designed to protect them from meningitis, HPV cancers, and whooping cough.”[27]

Promote information and resources about long-term care and survivorship

- Promote tailored resources, including individualized care plans.

- Address psychological support and needs by providing resources and referrals proactively for cervical cancer survivors.

- Address sexual and reproductive health needs by proactively sharing resources and referrals for management of long term side effects. For more information on survivorship, check out the GW Cancer Center’s Sexual Health and Cancer Survivorship lesson.

When communicating about HPV vaccination to parents, it is important to:

- Make strong and presumptive recommendations to parents, rooted in evidence about the positive benefits of the HPV vaccine.

- Integrate HPV vaccination into routine visits: recommend the HPV vaccine on the same day as other adolescent vaccines.[28]

- Listen to parental concerns, addressing questions and concerns about HPV vaccine.

- Emphasize the vaccine’s importance, clearly stating that the HPV vaccine significantly reduces the risk of several cancers, including cervical cancer.

- Approach discussions about the HPV vaccine the same way other adolescent vaccinations are framed, avoiding language that implies the HPV vaccine is optional.

- Use motivational interviewing techniques with hesitant parents to encourage vaccination, tailoring the conversation to specific concerns and knowledge levels while respecting their beliefs.[29]

When communicating about cervical cancer screening, health providers should:

- Provide specific instructions about cervical cancer screenings and ask patients to describe instructions afterwards to ensure understanding.[30]

- Ensure opportunities for patients to ask questions about screening, including prompting patients to ask questions by saying: “is there anything we haven’t covered yet?”[31]

- Recommend follow-up and specialist care with specific information and recommendations. Provider recommendations are positively associated with screening rates.[32]

- Take time for patients to share their thoughts and feelings and implement opportunities for shared decision making. Psychological distress may influence healthcare avoidance behaviors, so provide opportunities to enhance communication to prevent avoidance of screening.[33]

Share information about long-term care and survivorship.

- Promote tailored resources and proactive referrals for survivorship needs, including psychological support and sexual or reproductive health needs.

- Continue lifelong learning with resources like the GW Cancer Survivorship educational offerings and guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

Communicating with Diverse Audiences

Certain groups experience higher disparities in cervical cancer screening, incidence, mortality, and survival.[34] Cancer health disparities are complex and affected by various factors, such as social determinants of health, behavior, biology, genetics, and more.[35] Many individuals may experience unique intersections and marginalization of their social identities: this is referred to as intersectionality. Consider the information most useful to diverse groups in your audience.

Despite widely available screening tests and vaccinations, racial and ethnic disparities in cervical cancer survival rates continue to exist.[36] Therefore, it is important to tailor communication to these groups with messaging that also addresses conditions where people live, learn, work, and play, as these factors can impact a wide range of health risks and outcomes.

Below you will find considerations for audiences who experience disparities in cervical cancer screening access and care.

Cervical Cancer Resources

| Resource | Description |

|---|---|

| American Indian Cancer Foundation, Cervical Cancer | AICAF is a national Native-led and Native-governed nonprofit organization established to address the tremendous cancer burdens faced by Native people. Its mission is to eliminate the cancer burdens on American Indian and Alaska Native people through improved access to prevention, early detection, treatment, and survivor support. |

| ACS National HPV Roundtable Resources | The HPVRT Resource Center hosts resources developed as well as resources developed by our members and partners. The Resource Center does not provide an exhaustive catalog, but rather provides a sampling of key resources and tools that we believe will be most useful to improving HPV vaccination initiation and completion rates. |

| CDC Cervical Cancer Screening | CDC offers scientifically accurate information about cervical cancer in a variety of formats, including tools, resources, and graphics. |

| CDC HPV Vaccine Information | Various resources from the CDC provide information on HPV, the HPV vaccine, and HPV- related cancers. |

| Cervical Cancer Awareness Month Bilingual Infographics | These bilingual infographics highlight cervical cancer disparities, raise awareness, and emphasize the importance of screening. |

| Cervical Cancer Screening Preferences Among Transgender Individuals | This study conducted interviews with transgender individuals on perceptions and experiences of cervical cancer screening. They found that self-collected frontal HPV swabs were the preferred method of cancer screening among the participants. |

| Cervical Cancer Survivor Stories | CDC published a collection of personal cervical cancer survivor stories. Their first-hand accounts offer important lessons. |

| Cervical Cancer Survivorship Plan – Foundation for Women’s Cancer and Society of Gynecologic Oncology | For survivors and providers, a customizable resource to determine follow-up care and to get referrals for sexual and reproductive health needs. |

| Cervivor | Cervivor is the leading global patient advocacy nonprofit committed to cervical cancer awareness, support, and advocacy. |

| Closing in on the Bull’s Eye: Moving from Volume to Value through HPV Vaccination | Published in the American Medical Group Association’s Group Practice Journal, this article by AMGA and the National HPV Vaccination Roundtable makes the case for why health systems hold the key to preventing and eliminating HPV cancers. |

| Guide for Cancer Screening | This resource creates a personalized guide for LGBTQI+ cancer screening. |

| Federal Cervical Cancer Collaborative (FCCC) | The Federal Cervical Cancer Collaborative (FCCC) develops resources to advance equitable cervical cancer prevention, screening, and management in safety-net settings. Safety-net settings are places where people with limited or no insurance can receive care. People who are low-income can access services, as well. Two toolkits can serve your program and partners and are available in Spanish as well: Improving Cervical Cancer Prevention, Screening and Management: A Toolkit to Improve Provider Capacity and Improving Patient Engagement in Cervical Cancer Prevention: Communication Toolkit for Health Centers and Safety-net Settings of Care. |

| HPV IQ-Immunization Quality Improvement Tools | The site is designed for public health professionals and primary care providers who want to increase and improve the delivery of the HPV vaccine to adolescents. It provides evidence-based tools and strategies for quality improvement and communication training. |

| HPV VAX NOW Campaign | The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) Office on Women’s Health (OWH) developed the HPV VAX NOW campaign with the long-term goal of increasing HPV vaccination rates among young adults ages 18–26 living in Mississippi, South Carolina, and Texas. The campaign aims to help young adults in these states recognize the importance of the HPV vaccine as well as help providers effectively recommend the vaccine. Campaign web pages include guidance, tips, resources and communication toolkits. |

| Increasing HPV Vaccinations for LGBTQ+ Patients | This free online course, offered by the Equality California Institute, outlines evidence-based, LGBTQ+-sensitive strategies for increasing HPV vaccination rates among adolescents. This curriculum engages and trains healthcare workers in evidence-based, LGBTQ+-sensitive practices to encourage HPV vaccination, and to increase HPV vaccination rates among LGBTQ+ populations, particularly transgender and gender-nonconforming youth. |

| Inside Knowledge About Gynecologic Cancer Campaign | This CDC campaign raises awareness of the five main types of gynecologic cancer: cervical, ovarian, uterine, vaginal, and vulvar. It encourages individuals to pay attention to their bodies, so they can recognize any warning signs and seek medical care. |

| National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP) | Through the NBCCEDP, CDC helps individuals with low incomes who are uninsured or underinsured gain access to timely breast and cervical cancer screening, diagnostic, and treatment services. NBCCEDP also provides patient navigation services to help overcome barriers and get timely access to quality care. The National Report provides data on cancer screening by the program over an 11-year period. |

| National Cervical Cancer Coalition – Sex & Intimacy After Cervical Cancer | For survivors, an educational resource on sexual and reproductive health needs after cervical cancer treatment. |

| National Cervical Cancer Roundtable (NRTCC) | The American Cancer Society National Cervical Cancer Roundtable is a coordinated effort to accelerate the elimination of cervical cancer by addressing health disparities. |

| National HPV Vaccination Roundtable | The National HPV Vaccination Roundtable of 70 organizations working at the intersection of immunization and cancer prevention. |

| National LGBT Cancer Network: Cervical Cancer Card | This card aims to raise awareness about cervical cancer among members of the LGBTQ+ community. There are also cards that address the need for taking care of an individual’s physical and mental health. |

| National LGBT Cancer Network: Provider Database | A provider directory with a national listing of primary care doctors and cancer screening and treatment facilities around the country ranked based on their commitment to creating a safe and welcoming environment. Look for factors like website presence, LGBTQI+ staff training, and transgender care in the complete Welcoming Provider Criteria & Ranking |

| NPAIHB HPV Vaccination Toolkit | This resource guide from the Northwest Portland Area Indian Health Board provides information for providers of Native and Indigenous patients to prevent HPV and HPV-related cancers. |

| St. Jude HPV Cancer Prevention Program | The St. Jude HPV Cancer Prevention Program aims to reduce HPV-associated cancer deaths. They have hosted webinars focused on reaching various populations, including people who live in rural areas and Native and Indigenous communities. |

| GW Cancer Center: Together, Equitable, Accessible, Meaningful (TEAM) Training | This training aims to improve health equity by supporting organizational changes at the systems level. The training will help organizations implement quality improvements to advance equitable, accessible and patient-centered cancer care through improved patient-provider communication, cultural sensitivity, shared decision-making, and attention to health literacy. |

| Us vs. HPV 2020 | This webinar series is hosted by the American Medical Women’s Association, Global Initiative Against HPV and Cervical Cancer, and Indiana University’s National Center of Excellence in Women’s Health. The webinars are intended for members of the public, patients, healthcare providers, and anyone else who wishes to learn more about various aspects of HPV-related diseases and HPV prevention. |

| What Works: Increasing Cervical Cancer Screenings for Hispanics and AANHPI Communities | This webinar, in collaboration with the Nuestras Voces Network, highlights resources to support efforts for cervical cancer education and prevention, and presents examples of implemented interventions in Hispanic and Asian and Pacific Islander communities. |

Cervical Cancer Awareness Month Messages and Graphics

Twitter/X

Download All Messages and Graphics

Social media management tools like Hootsuite and Sprout Social offer bulk scheduling options for uploading multiple messages at once. The spreadsheet below can be adapted to fit multiple scheduling platforms or services. It is currently formatted to work with Sprout Social’s bulk scheduling option. Please review the bulk scheduling format requirements for your specific platform before posting. Messages are sorted by network.

Download All Twitter, Facebook or LinkedIn Messages

Download All Instagram Messages

If you would like to download all images in this social media toolkit, click on each network below for a zip file with each network’s graphics. Please note that these image sizes are slightly smaller than the links above due to file size limitations. If you would like to download full resolution versions, simply click on the “Download Graphic” link below each image in the message tables above.

Template Graphics

Need to adjust our designs? Use our Canva Templates for GW TAP’s Breast Cancer Awareness Month Graphics

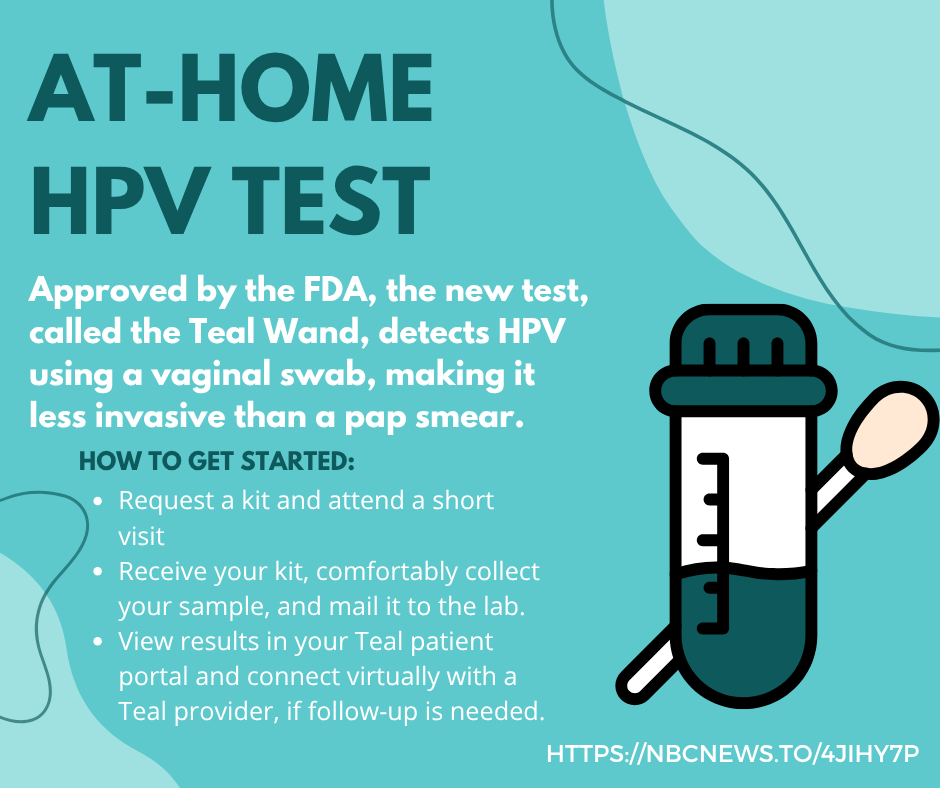

*New* HPV Screening At-Home Message Set

In light of the recent FDA approval and availability of the at-home self-sampling HPV screening option, the GW Cancer Center developed timely messaging if your program needs to provide clarity and encouragement for this new option. You can download this entire message and graphics set as you need.

Files for X (Twitter), Facebook and LinkedIn

Files for Instagram

| Message | Graphic |

| Testing for HPV is getting easier. A new at-home HPV screening kit is FDA-approved and designed for privacy and convenience. It will be available by prescription, through a telehealth service, for people with a cervix who are 25-65 years old, and of average risk. Learn more at: https://nbcnews.to/4jiHY7P |  |

| Soon you can test for HPV from the comfort of your own home! It’s private, easy, and a step toward preventing cervical cancer. Read more about it! https://nbcnews.to/4jiHY7P |  |

| Taking charge of your health has never been easier. With at-home HPV tests, you can screen privately and conveniently. Detecting high-risk HPV early can make all the difference. |  |

| Did you know that most cervical cancers are preventable? With at-home HPV tests, you can screen privately and conveniently. No clinic visit required. Detecting high-risk HPV early can make all the difference. Whether you’re overdue for a Pap test or prefer the comfort of home, self-collection is a proven, FDA-approved option and can be a game-changer in early detection. |  |

| The FDA has recently approved an at-home HPV test! The new test, called the Teal Wand, detects HPV using a vaginal swab, making it less invasive than a pap smear. Read more: https://nbcnews.to/4jiHY7P |  |

| The FDA has recently approved an at-home HPV test! The new test, called the Teal Wand, detects HPV using a vaginal swab, making it less invasive than a pap smear. Read more at: https://nbcnews.to/4jiHY7P |  |

Footnotes

1. U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2024). United States Cancer Statistics Working Group, U.S. Cancer Statistics Data Visualizations Tool, based on 2021 submission data. Retrieved from https://gis.cdc.gov/Cancer/USCS/DataViz.html.

2. U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group, 2024.

3. U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group, 2024.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). Screening for Cervical Cancer. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/cervical-cancer/screening/index.html

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2023.

6. U.S. Preventative Taskforce. (2024). U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Issues Draft Recommendation Statement on Screening for Cervical Cancer Women ages 21 to 65 should get screened regularly for cervical cancer.https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/sites/default/files/file/supporting_documents/cervical-cancer-screening-draft-rec-bulletin_0.pdf

7. National Cancer Institute. (2024). FDA Approves HPV Tests That Allow for Self-Collection in a Health Care Setting. https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog/2024/fda-hpv-test-self-collection-health-care-setting

8. National Cancer Institute. (2024). Cervical Cancer Screening. retrieved from: https://www.cancer.gov/types/cervical/screening

9. Fuzzell, L. N., Perkins, R. B., Christy, S. M., Lake, P. W., & Vadaparampil, S. T. (2021). Cervical cancer screening in the United States: Challenges and potential solutions for underscreened groups. Preventive Medicine, 144, 106400–106400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106400

10. Haas, J. S., Vogeli, C., Yu, L., Atlas, S. J., Skinner, C. S., Harris, K. A., Feldman, S., & Tiro, J. A. (2021). Patient, provider, and clinic factors associated with the use of cervical cancer screening. Preventive medicine reports, 23, 101468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101468

11. Johnson, N. L., Head, K. J., Scott, S. F., & Zimet, G. D. (2020). Persistent Disparities in Cervical Cancer Screening Uptake: Knowledge and Sociodemographic Determinants of Papanicolaou and Human Papillomavirus Testing Among Women in the United States. Public health reports (Washington, D.C.:1974), 135(4), 483–491. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033354920925094

12. Spencer, J. C., Kim, J. J., Tiro, J. A., Feldman, S. J., Kobrin, S. C., Skinner, C. S., Wang, L., McCarthy, A. M., Atlas, S. J., Pruitt, S. L., Silver, M. I., & Haas, J. S. (2023). Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Cervical Cancer Screening From Three U.S. Healthcare Settings. American journal of preventive medicine, 65(4), 667–677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2023.04.016

13. Spencer et al., 2023.

14. Centers Disease Control and Prevention (2024). Find a Screening Program Near You. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/breast-cervical-cancer-screening/about/screenings.html#cdc_generic_section_1-are-you-eligible-for-free-or-low-cost-screenings

15. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2024). Basic Information about HPV and Cancer. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/basic-information.html

16. CDC, 2024.

17. American Cancer Society (2024). HPV Vaccines. Retrievd from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/risk-prevention/hpv/hpv-vaccines.html

18. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2024). Impact of the HPV Vaccine. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/vaccination-impact/index.html

19. Oh, N. L., Biddell, C. B., Rhodes, B. E., & Brewer, N. T. (2021). Provider communication and HPV vaccine uptake: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Preventive medicine, 148, 106554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106554 ; Kong, W. Y., Bustamante, G., Pallotto, I. K., Margolis, M. A., Carlson, R., McRee, A. L., & Gilkey, M. B. (2021). Disparities in Healthcare Providers’ Recommendation of HPV Vaccination for U.S. Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology, 30(11), 1981–1992. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-21-0733

20. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2024). Clinical Information about HPV. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/hcp/clinical-overview/index.html

21. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2024). ACIP Recommendations: Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccine. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/acip-recs/hcp/vaccine-specific/hpv.html

22. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2024). Gardasil 9; Human Papillomavirus 9-valent Vaccine. Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/vaccines/gardasil-9

23. American Academy of Pediatrics. (2023). Human Papillomavirus (HPV). Retrieved from https://www.aap.org/en/news-room/campaigns-and-toolkits/human-papillomavirus-hpv/?srsltid=AfmBOopoJJ4Wx6dNG78nzY_NGPnYzWGjAXd0MZt7X2OQOjwMB4DIC-OJ .

24. Vielot NA, Brewer NT. (2024). Optimizing Cancer Prevention in Adolescents by Improving HPV Vaccine Delivery. North Carolina Medical Journal, 85(1). doi:10.18043/001c.91426

25. American Cancer Society (2024). HPV Vaccines. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/risk-prevention/hpv/hpv-vaccines.html

26. Fuzzell et al., 2021.

27. American Cancer Society. (2020). Steps for Increasing HPV Vaccination in Practice: An Action Guide to Implement Evidence-based Strategies for Clinicians. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/online-documents/en/pdf/flyers/steps- for-increasing-hpv-vaccination-in-practice.pdf

28. Constable, C., Ferguson, K., Nicholson, J., & Quinn, G. P. (2022). Clinician communication strategies associated with increased uptake of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine: A systematic review. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians, 72(6), 561–569. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21753

29. American Psychological Association. (2020). APA Dictionary of Psychology: motivational interviewing. Retrieved from https://dictionary.apa.org/motivational-interviewing ; Gagneur A. (2020). Motivational interviewing: A powerful tool to address vaccine hesitancy. Canada communicable disease report = Releve des maladies transmissibles au Canada, 46(4), 93–97. https://doi.org/10.14745/ccdr.v46i04a06

30. Kindratt, T. B., Dallo, F. J., Allicock, M., Atem, F., & Balasubramanian, B. A. (2020). The influence of patient-provider communication on cancer screenings differs among racial and ethnic groups. Preventive medicine reports, 18, 101086. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2020.101086

31. Ajayi, K. V., Panjwani, S., Garney, W., & McCord, C. E. (2022). Sociodemographic factors and perceived patient-provider communication associated with healthcare avoidance among women with psychological distress. PEC innovation, 1, 100027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pecinn.2022.100027

32. Fuzzell et al., 2021.

33. Ajayi et al., 2022.

34. National Cancer Institute. (2020). Cancer disparities. Retrieved August 11, 2021 from https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/understanding/disparities

35. NCI, 2020.

36. Johnson, N. L., Head, K. J., Scott, S. F., & Zimet, G. D. (2020). Persistent Disparities in Cervical Cancer Screening Uptake: Knowledge and Sociodemographic Determinants of Papanicolaou and Human Papillomavirus Testing Among Women in the United States. Public health reports (Washington, D.C.:1974), 135(4), 483–491. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033354920925094

37. Cohen, C. M., Wentzensen, N., Castle, P. E., Schiffman, M., Zuna, R., Arend, R. C., & Clarke, M. A. (2023). Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Cervical Cancer Incidence, Survival, and Mortality by Histologic Subtype. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, 41(5), 1059–1068. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.22.01424

38. Ford, S., Tarraf, W., Williams, K. P., Roman, L. A., & Leach, R. (2021). Differences in cervical cancer screening and follow-up for black and white women in the United States.Gynecologic Oncology, 160(2), 369–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2020.11.027

39. Ford et al., 2021.

40. Ford et al., 2021.

41. Office of Minority Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2021). Cancer and Hispanic Americans. Retrieved from https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=4&lvlid=61

42. American Cancer Society. (2024). Cancer Facts & Figures for Hispanic/Latino People 2024-2026 Atlanta: American Cancer Society, Inc. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/hispanics-latinos-facts-figures.html

43. American Cancer Society, 2024.

44. Lee, R.J., Madan, R. A., Kim, J., Posadas, E. M., & Yu, E. Y. (2021). Disparities in Cancer Care and the Asian American Population. The Oncologist (Dayton, Ohio), 26(6), 453–460. https://doi.org/10.1002/onco.13748

45. Lee et al., 2021.

46. Zhu, D. T., Lai, A., Park, A., Zhong, A., & Tamang, S. (2024). Disparities in Cancer Mortality among Disaggregated Asian American Subpopulations, 2018-2021. Journal of racial and ethnic health disparities, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-024-02067-0

47. Zhu et al., 2024.

48. Ho, F. D. V., Thaploo, A., Wang, K., Narayan, A., Alberto, I. R. I., Ong, E. P., Kohli, K., Kohli, M., Jain, B., Dee, E. C., Gomez, S. L., Janopaul-Naylor, J., & Chino, F. (2024). Cervical cancer disparities in stage at presentation for disaggregated Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology, S0002-9378(24)00867-6. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2024.08.027

49. Ho et al., 2024.

50. Office of Minority Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2021). Cancer and Native Hawaiians/Pacific Islanders. Retrieved from https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/cancer-and-native-hawaiianspacific-islanders

51. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). Cancer Distribution Among Asian, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander Subgroups — United States, 2015–2019. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/72/wr/mm7216a2.htm

52. CDC, 2023.

53. Bruegl, A. S., Emerson, J., & Tirumala, K. (2023). Persistent disparities of cervical cancer among American Indians/Alaska natives: Are we maximizing prevention tools?. Gynecologic oncology, 168, 56–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2022.11.007

54. Lee, Y.S., Roh, S., Jun, J. S., Goins, R. T., & McKinley, C. E. (2021). Cervical cancer screening behaviors among American Indian women: Cervical cancer literacy and health belief model. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 30(5), 413–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/15313204.2020.1730285

55. Zhang, M., Sit, J. W. H., Chan, D. N. S., Akingbade, O., & Chan, C. W. H. (2022). Educational Interventions to Promote Cervical Cancer Screening among Rural Populations: A Systematic Review. International journal of environmental research and public health, 19(11), 6874. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116874

56. Hirko, K. A., Xu, H., Rogers, L. Q., Martin, M. Y., Roy, S., Kelly, K. M., Christy, S. M., Ashing, K. T., Yi, J. C., Lewis-Thames, M. W., Meade, C. D., Lu, Q., Gwede, C. K., Nemeth, J., Ceballos, R. M., Menon, U., Cueva, K., Yeary, K., Klesges, L. M., Baskin, M. L., … Ford, S. (2022). Cancer disparities in the context of rurality: risk factors and screening across various U.S. rural classification codes. Cancer causes & control : CCC, 33(8), 1095–1105. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-022-01599-2

57. Zhang et al., 2022.

58. Lee, H., Baeker Bispo, J., Pal Choudhury, P., Wiese, D., Jemal, A., & Islami, F. (2024). Factors contributing to differences in cervical cancer screening in rural and urban community health centers. Cancer, 130(13), 2315–2324. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.35265

59. Kong, W. Y., Bustamante, G., Pallotto, I. K., Margolis, M. A., Carlson, R., McRee, A. L., & Gilkey, M. B. (2021). Disparities in Healthcare Providers’ Recommendation of HPV Vaccination for U.S. Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology, 30(11), 1981–1992. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-21-0733

60. American Cancer Society. (2024). Cancer Fact Sheet for LGBTQ+ People. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, Inc. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/cancer-control/en/booklets-flyers/cancer-fact-sheet-for-lgbtq-people.pdf

61. ACS, 2024.

62. Heer, E., Peters, C., Knight, R., Yang, L., & Heitman, S. J. (2023). Participation, barriers, and facilitators of cancer screening among LGBTQ+ populations: A review of the literature. Preventive medicine, 170, 107478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2023.107478

63. Spencer, J. C., Brewer, N. T., Coyne-Beasley, T., Trogdon, J. G., Weinberger, M., & Wheeler, S. B. (2021). Reducing Poverty-Related Disparities in Cervical Cancer: The Role of HPV Vaccination. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology, 30(10), 1895–1903. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-21-0307

64. Spencer et al., 2021.

65. American Cancer Society (2024) HPV Vaccines. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/risk-prevention/hpv/hpv-vaccines.html

66. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Find a Screening Program Near You. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/breast-cervical-cancer-screening/about/screenings.html#cdc_generic_section_1-are-you-eligible-for-free-or-low-cost-screenings

67.Kong et al., 2021.